The fascination with Ancient Egypt and her artifacts has existed since the days of the ancient Romans, who carted monuments like giant obelisks back to Rome. (To this day, there are more obelisks in Rome than Egypt.)

Cleopatra testing poisons on condemned prisoners, Alexandre Cabanel, 1887, Royal Museum of...

The desire to both possess a piece of that culture — and to be creatively inspired by it — has persisted for millennia.

Cleopatra, Thomas Francis Dicksee, 1863 (sold at Bonhams, September 2019 for ...

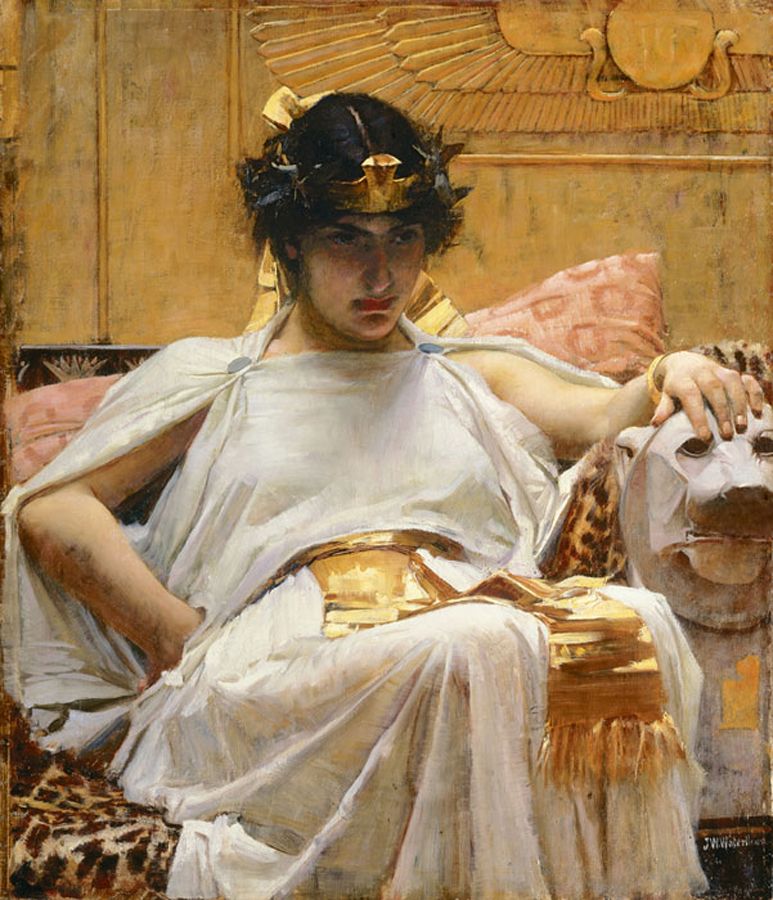

Cleopatra, John William Waterhouse, 1887.

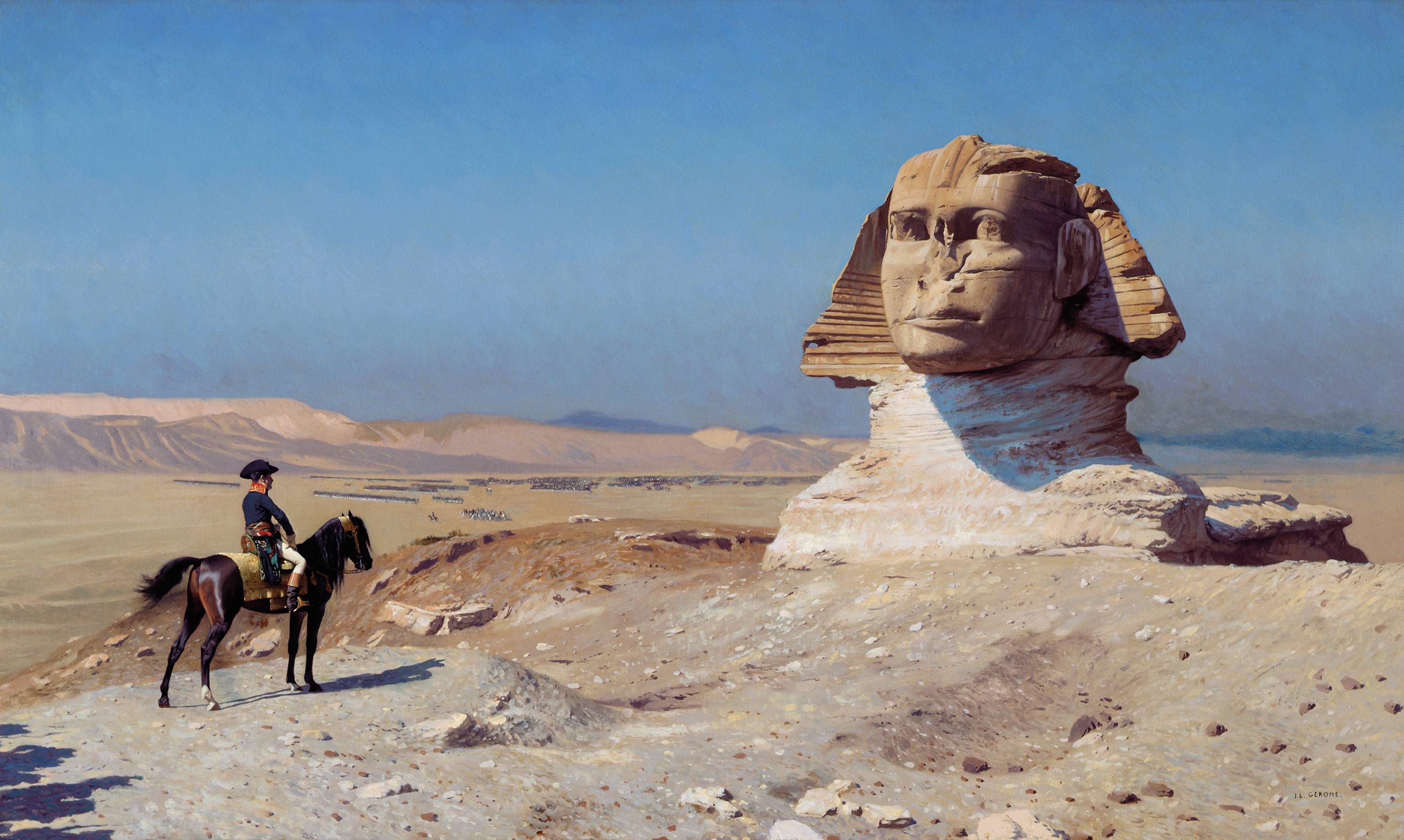

Let’s fast-forward to the end of the 18th century, when Egyptomania developed to a fever pitch. In 1798, Napoleon invaded Egypt. (His beef was with the British and the impact their rapid colonization was having on trade channels). The chance to also explore the Egyptian continent seemed like a “two birds with one stone” opportunity. So along with his army, Napoleon took a team of 150 scientists, engineers, soldiers and scholars who were responsible for documenting and “collecting” Egyptian culture and history.

Francois-Louis-Joseph Watteau’s depiction of the Battle of the Pyramids.

Bonaparte Before the Sphinx, Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1886, Hearst Castle.

The fate of the army was tragic. Few of the 34,000 men that Napoleon took to Egypt made it home. But for those documenting Egyptian culture, it was a huge success. One of their discoveries was the Rosetta Stone, which would unlock the mystery of hieroglyphics and create the field of Egyptology.

International Congress of Orientalists: The Rosetta Stone at the British Museum, 1874.

As part of the agreement following the French defeat, all antiquities acquired on the expedition were sent to England, and they all — including the Rosetta Stone — eventually ended up in the British Museum. (Egypt is still requesting the return of the Rosetta Stone and other objects of cultural significance. The British Museum has said it has no plans to repatriate stolen artifacts. It’s not only the British Museum, either — National museums around the world were built on the backs of this type of exploitive exploration and straight-up theft of ancient artifacts.)

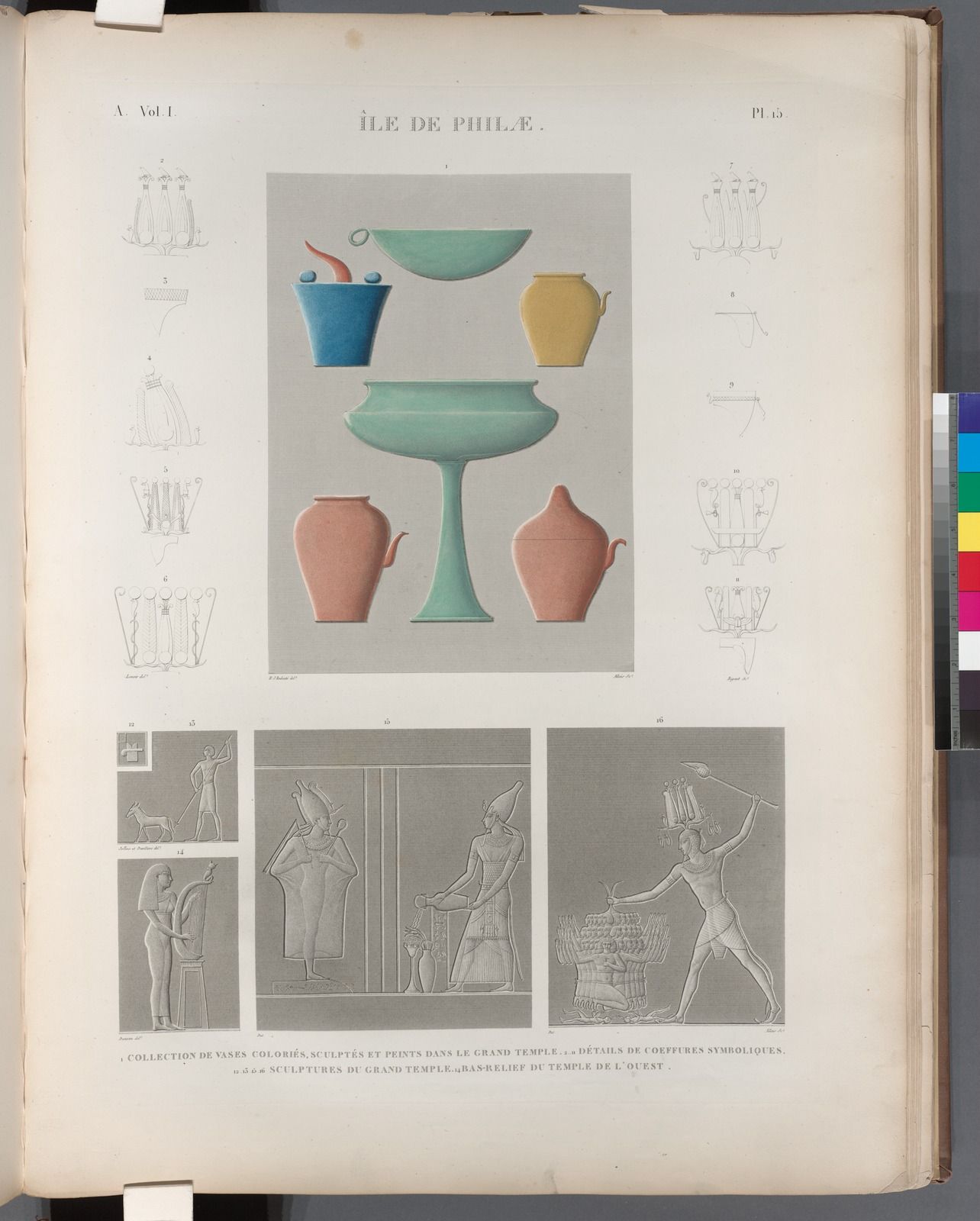

The French scholars spent years drawing and documenting their findings. And in 1809, they published the first volume of Description de l’Egypte. (Flip through it on the New York Public Library’s digital collection.) This series and the many books that followed became an invaluable resource for the burgeoning field of Egyptology as well as an inspiration source for artists, architects and designers who were captivated by the those ancient motifs. In the ensuing decades, new archeological finds, the Suez canal, and cultural events like Giuseppe Verdi’s extraordinarily popular opera Aida kept Ancient Egypt in the public consciousness.

Plate from Description de l'Égypte, 1809, The New York Public Library.

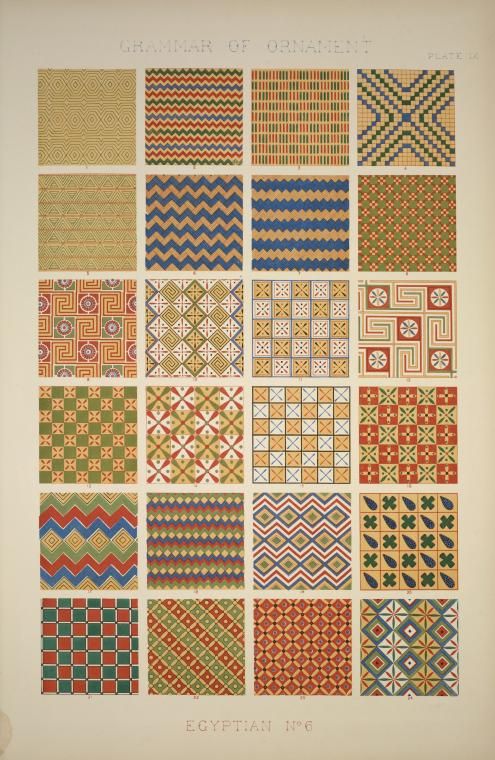

Egyptian no. 6; geometrical ornaments from ceilings of tombs, Grammar of Ornament,...

Remember, Egyptian Revival was a form of Orientalism, a Western patronizing fascination with a perceived exoticism found in all corners of the East: Japanese culture (Japonisme), Chinese culture (Chinoiserie) and the Ottoman empire (Turquerie). When examined with a modern sensibility, some of the resulting art is exploitative and derivative, and some have a more nuanced approach and use the Eastern motifs to create something entirely new — not Eastern or Western, but the best of both.

Orientalism — and Egyptian Revival — wasn’t concerned with respectfully or even truthfully depicting foreign culture, but rather borrowing motifs and vibes loosely.

Center Table, 1870–75, attributed to Pottier and Stymus Manufacturing Company, NYC.

Egyptian Revival demi-parure, c 1865, Carlo Giuliano, in the collection of the...

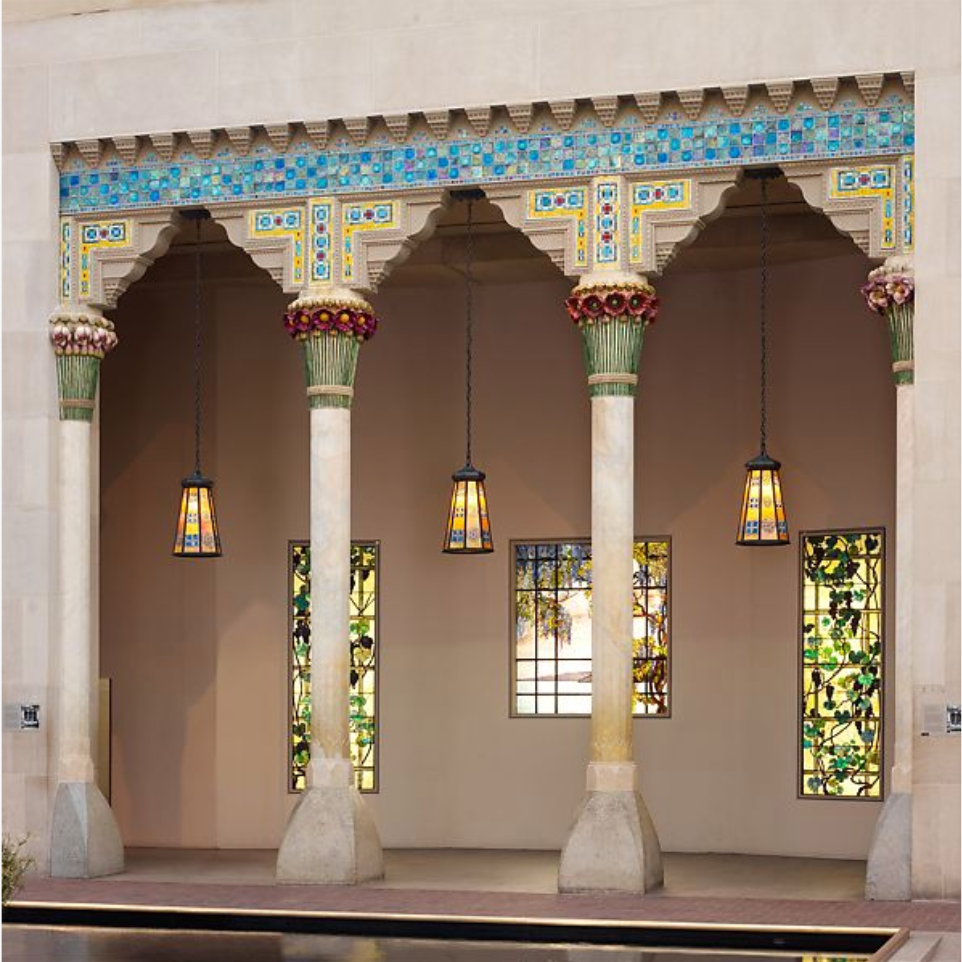

The vocabulary of Egyptian antiquities was adapted with a sense of wonder and fun; it was all tossed in a blender with other aesthetics of the day. Scarabs, pyramids and sarcophagi were mixed up with geometric patterns coming up in the Deco era, natural themes of the Aesthetic movement, and Neoclassicism. When Louis Comfort Tiffany designed his Long Island home between 1902 and 1905, he incorporated many Egyptian-ish designs into the architecture, like lotus-flower columns. His popular mantelpiece clock featured obelisks and sphinxes with absolutely made-up heiroglyphics; they would make an archaeologist cringe.

Architectural Elements from Laurelton Hall, Oyster Bay, New York ca. 1905. Designed...

Clock ca. 1885, Tiffany & Co.

Then came Howard Carter’s discovery. An English archaeologist, he had been working in Egypt since he was seventeen. In 1922, Carter (he was 48) had been working for several years without much luck when his water boy stumbled on a stone that turned out to be the steps to Tutankhamun’s tomb.

Howard Carter (center) looking inside an Egyptian tomb, colorized by Dynamichrome.

Tutankhamun’s Tomb, October 1925, Howard Carter working on the lid of the...

On November 26, 1922, in front of an audience that included financial backer Lord Carnarvon, Carnarvon’s daughter and others, Carter made a “tiny breach in the top left hand corner of the doorway” and with the light of a candle peered into the tomb. He had discovered the best preserved pharoanic tomb ever found in the Valley of the Kings.

Vanity case, Egyptian sarcophagus, Cartier, 1925, Cooper-Hewitt Museum.

Scarab belt buckle, 1926, Cartier, Cooper-Hewitt Museum.

Clearing the tomb of thousands of objects continued until 1932. Those uncovered objects would provide endless inspiration for Art Deco artists and designers, and the story of the discovery of King Tut’s tomb would provide limitless fodder for Hollywood.

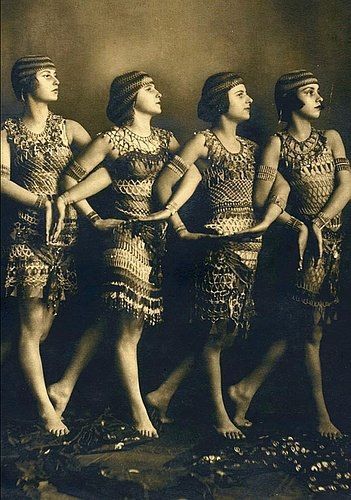

Flappers, ca. 1920s.

The cultural impact of that discovery continued until the end of the 20th century thanks to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, who wanted to forge a strong diplomatic partnership with Egypt. He hoped to shore up goodwill between the countries through a cultural exchange. The US agreed to help the Egyptians reconstruct Cairo's opera house, while Egypt would lend a collection of artifacts from Tutankhamun’s tomb to the United States.

From November 1976 through April 1979, the “Treasures from King Tutankhamun’s Tomb” show traveled to six American cities. The exhibition was a blockbuster. Millions of people lined up to see the shows and spent hundreds of thousands on King Tut souvenirs. (The exhibition was revived in 2019 and was set to continue until 2023. It has currently been postponed.)

Theatrical poster for Cleopatra, 1963.

Lyndsey Marshal as Cleopatra in the HBO series “Rome,” 2005-2007.

There is still so much to be uncovered in Egypt, making it likely that the biggest Egyptian revival is still ahead of us. Just imagine the discovery of the lost tombs of Cleopatra and Mark Antony! Since 2005, Kathleen Martínez has been one of the archeologists leading efforts to find the couple’s tombs. As recently as 2021, Martínez and her team discovered 2,000 year old ancient tombs with golden tongues dating to the Greek and Roman periods.